Portal:Stars

IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime as a fusor, its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: Digitized Sky Survey, NASA

Arcturus (/ɑːrkˈtjʊərəs/; α Boo, α Boötis, Alpha Boötis) of the constellation Boötes is the brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere. With a visual magnitude of −0.04, it is the fourth brightest star in the night sky, after −1.46 magnitude Sirius, −0.86 magnitude Canopus, and −0.27 magnitude Alpha Centauri. It is a relatively close star at only 36.7 light-years from Earth, and, together with Vega and Sirius, one of the most luminous stars in the Sun's neighborhood. Arcturus is a type K0 III orange giant star, with an absolute magnitude of −0.30. It has likely exhausted its hydrogen from its core and is currently in its active hydrogen shell burning phase. It will continue to expand before entering horizontal branch stage of its life cycle. Arcturus is a type K0 III Red giant star. It is at least 110 times more luminous than the Sun in visible light wavelengths, but this underestimates its strength as much of the "light" it gives off is in the infrared; total (bolometric) power output is about 180 times that of the Sun. The lower output in visible light is due to a lower efficacy as the star has a lower surface temperature than the Sun. As the brightest K-type giant in the sky, it was the subject of an atlas of its visible spectrum, made from photographic spectra taken with the coudé spectrograph of the Mt. Wilson 2.5m telescope published in 1968, a key reference work for stellar spectroscopy. Selected article - Photo credit: User:Nikolang

A white dwarf, also called a 'degenerate dwarf, is a small star composed mostly of electron-degenerate matter. They are very dense; a white dwarf's mass is comparable to that of the Sun and its volume is comparable to that of the Earth. Its faint luminosity comes from the emission of stored thermal energy. In January 2009, the Research Consortium on Nearby Stars project counted eight white dwarfs among the hundred star systems nearest the Sun. The unusual faintness of white dwarfs was first recognized in 1910 by Henry Norris Russell, Edward Charles Pickering, and Williamina Fleming; the name white dwarf was coined by Willem Luyten in 1922. White dwarfs are thought to be the final evolutionary state of all stars whose mass is not high enough to become a neutron star—over 97% of the stars in our galaxy. After the hydrogen–fusing lifetime of a main-sequence star of low or medium mass ends, it will expand to a red giant which fuses helium to carbon and oxygen in its core by the triple-alpha process. If a red giant has insufficient mass to generate the core temperatures required to fuse carbon, around 1 billion K, an inert mass of carbon and oxygen will build up at its center. After shedding its outer layers to form a planetary nebula, it will leave behind this core, which forms the remnant white dwarf. Usually, therefore, white dwarfs are composed of carbon and oxygen. If the mass of the progenitor is above 8 solar masses but below 10.5 solar masses, the core temperature suffices to fuse carbon but not neon, in which case an oxygen-neon–magnesium white dwarf may be formed.appear to have been formed by mass loss in binary systems. The material in a white dwarf no longer undergoes fusion reactions, so the star has no source of energy, nor is it supported by the heat generated by fusion against gravitational collapse. It is supported only by electron degeneracy pressure, causing it to be extremely dense. The physics of degeneracy yields a maximum mass for a non-rotating white dwarf, the Chandrasekhar limit—approximately 1.4 solar mass—beyond which it cannot be supported by electron degeneracy pressure. A carbon-oxygen white dwarf that approaches this mass limit, typically by mass transfer from a companion star, may explode as a Type Ia supernova via a process known as carbon detonation. Selected image - Photo credit: NASA/Walt Feimer

According to the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, a red dwarf is a small and relatively cool star, of the main sequence, either late K or M spectral type. They constitute the vast majority of stars and have a mass of less than half that of the Sun (down to about 0.075 solar masses, which are brown dwarfs) and a surface temperature of less than 4,000 K. Did you know?SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

Selected biography - Photo credit: By Justus Sustermans

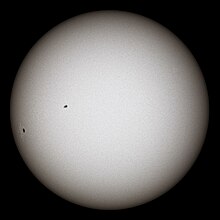

Galileo Galilei (Italian pronunciation: [galiˈlɛo galiˈlɛi]; 15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations, and support for Copernicanism. Galileo has been called the "father of modern observational astronomy", the "father of modern physics", the "father of science", and "the father of modern science". Stephen Hawking says: "Galileo, perhaps more than any other single person, was responsible for the birth of modern science." The motion of uniformly accelerated objects, taught in nearly all high school and introductory college physics courses, was studied by Galileo as the subject of kinematics. His contributions to observational astronomy include the telescopic confirmation of the phases of Venus, the discovery of the four largest satellites of Jupiter (named the Galilean moons in his honour), and the observation and analysis of sunspots. Galileo also worked in applied science and technology, inventing an improved military compass and other instruments. Galileo's championing of Copernicanism was controversial within his lifetime, when a large majority of philosophers and astronomers still subscribed (at least outwardly) to the geocentric view that the Earth is at the centre of the universe. After 1610, when he began publicly supporting the heliocentric view, which placed the Sun at the centre of the universe, he met with bitter opposition from some philosophers and clerics, and two of the latter eventually denounced him to the Roman Inquisition early in 1615. In February 1616, although he had been cleared of any offence, the Catholic Church nevertheless condemned heliocentrism as "false and contrary to Scripture", and Galileo was warned to abandon his support for it—which he promised to do. When he later defended his views in his most famous work, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published in 1632, he was tried by the Inquisition, found "vehemently suspect of heresy", forced to recant, and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |